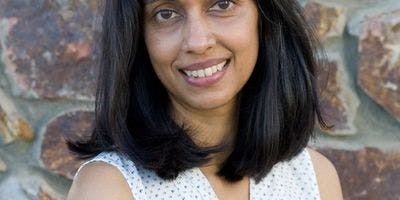

In Orange for the Sunsets, author Tina Athaide draws on her own experience and that of family and friends living in Uganda in the 1970s. The result is an enthralling, eye opening work of historical fiction.

Bookroo: Hi Tina, it’s so nice to visit with you.

Tina Athaide: Hello Chandler, thank you for the invitation. I am very excited to visit with the Bookroo team and community.

We were delighted to feature your book, Orange for the Sunsets, in our middle grade chapter book box.

We found it to be a very captivating story with lessons relevant to today. So we’re excited to talk about it with you.

But before we get to this specific book, can you tell us a little about what was your journey to becoming an author of children’s books.

My writing journey can best be described in three words: Dream. Perseverance. Cake.

The real push to start writing came during the early years of my teaching career when I realized that there were few books that dealt with cultures outside of the white European experiences. So, I started writing and began with early readers like Pran’s Week of Adventure and Flora’s Box. I wanted my students to hold a book in their hands where they could see themselves in the pages, whether in the illustrations or pieces of the story.

And then the DREAM appeared . . .

. . . to write a book with bits of my own story and that of my family and friends.

So, I put pen to paper, or rather, fingers to laptop. You will find it interesting to learn that this story began as a picture book before shifting into a middle grade novel. Like a chameleon it changed many, many, many (did I say MANY) times. I was in the world of rewriting, just like when teachers have students complete a rough draft before turning in your final paper. One version was written only from Asha’s point of view and I tossed 100 pages into the bin and then started crafting Yesofu’s story.

Wow, fascinating that it began as a picture book and evolved into this—it works really well as a middle grade chapter book. That much reworking takes some serious perseverance.

Exactly. Lots of perseverance. The story was rejected 30 times before finding a home. This meant a lot of revisions, re-imagining, and rewriting. There were many times I tossed it in a drawer and wanted to give up . . . but I didn’t!

Thankfully not!

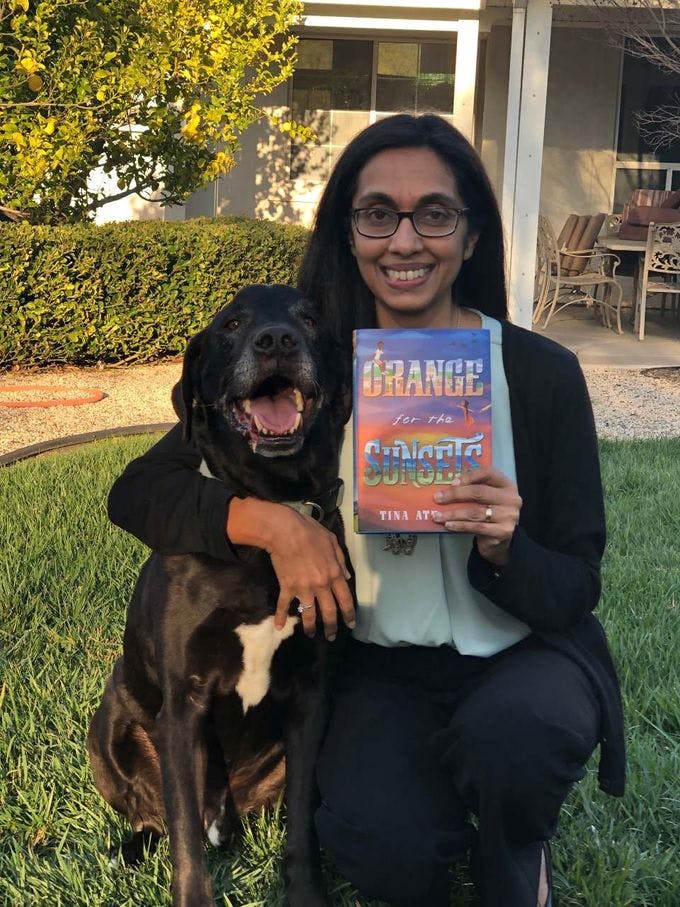

And then there's cake. I had plenty of cake on this journey:

- When I finished the book.

- When I sold the story.

- When I held it in my hands for the first time.

- When I saw it in bookshops.

- When I received my first letter from a young reader. (This was my FAVORITE cake day!)

As a teacher and writer, I believe that books have the power to open readers to new awareness and appreciation of differences in culture and experience and am honored to be a part of that journey for someone.

In Orange for the Sunsets, you explain in an Author’s Note how the book is based in large part on your own experiences and the stories you gathered from family and friends. Can you share more about that? Is Yesofu based on a true life friend you left behind?

This story is close to my heart. Orange for the Sunsets is set in Uganda, where I was born, and tells the story of Asha and Yesofu. Two friends who have never cared about their differences. Indian. African. Short. Tall. It's never mattered. But when Idi Amin announces that Indians have ninety days to leave the country, suddenly those differences are the only things people can see.

Determined for her life to stay the same, Asha clings to her world tighter than ever before. But Yesofu is torn, pulled between his friends, his family, and a promise of a better future. As neighbors leave and soldiers line the streets, the two friends find that nothing seems sure—not even their friendship.

Though my family's departure from Uganda was not as traumatic as the experiences depicted in the novel, I remember relatives arriving at our London home with one suitcase and fifty shillings, which is all they were allowed to take when they left.

Later, I attended a Ugandan reunion in Vancouver and was moved by how the community's joy, hope, and resilience empowered them to rebuild their lives in new countries.

I worried that this story might get lost and I knew it needed to be told. Asha and Yesofu are not based on any one specific person, but rather many people and experiences. Though in writing Orange for the Sunsets, Yesofu was my favorite and I often thought that I would have liked to have been best friends with him.

You really create a compelling, authentic friendship at the heart of the story. The meaning of the book’s title is so poignant. It doesn’t get revealed until near the end of the book, and when it is revealed, it’s at this heartbreaking moment, when it’s clear that the word “sunsets” refers, at least in part, to life’s sunsets—moments when one chapter ends and a new chapter begins. Was there a different working title for the story, or did you know all along this would be the title?

Well Chandler, this is an interesting story. From the start, the title of the story was Impossible Goodbyes. I loved that title and thought it was very clever. It referred to Asha’s goodbye to her country and home. Her goodbye to her friends and best friend, Yesofu. And finally, her goodbye to her father.

The editorial team felt Impossible Goodbyes sounded like the title of a romance novel and after some thought, I agreed. So in the bin it went—and a new title appeared. I will admit that I do love the title, Orange for the Sunsets, as it connects to so many things in the story. I loved your comparison between “life’s sunsets” and the title.

Even before the president’s expulsion order, Asha and Yesofu have started to realize that there are big differences between them—economic and societal differences—and they’re trying to decide whether those should matter. Why did you start the story with their friendship already in turmoil? It really seems to heighten the drama from the get go.

Friendship is a central theme running throughout the story. In those opening scenes, I really wanted to show the difference between Asha and Yesofu. The economic and social differences have always been present, but it is becoming more defined as they get older. This was an opportunity for Asha and Yesofu to show the reader a little bit of what matters to them. We see how Asha’s world of privilege makes her oblivious compared to Yesofu, who is very aware of what these differences mean to him, his future, and their friendship.

Yesofu’s dream of throwing the opening ball at the big game is interrupted by the president’s expulsion order. Is this the beginning of Yesofu’s realization that maybe the future his president has promised might not be so bright after all, or won’t be without negative impacts?

Throwing the ball at the cricket match is a big moment for Yesofu. President Amin’s arrival and announcement bring about conflicting emotions for Yesofu. There is the promise of a brighter future for Ugandan Africans and the idea of opportunities for his future and that of his family. However in the wake of the announcement, Yesofu sees the terror in the stands unfold as Asian Indians, including Asha, flee to get out of the park. That fear and panic is felt by Yesofu and it leaves him with questions and a feeling of uncertainty.

The expulsion seems to turn violent very quickly, with soldiers destroying property and beating individuals. Is that based on experiences you learned about?

This was a very violent period in history. I knew my readers were most likely ages 9-13, but to make this story authentic, I felt it was important to share some of the violence so readers would get a sense of the terror without having to read the details. The scenes described are based on true events and accounts from family, friends, and other people I interviewed.

Yesofu’s friend Akello leaves school to join the Ugandan military. He is ruthless and dangerous, even threatening Asha’s life when he traps her in a well, and presumably reporting to the Ugandan authorities about Asha’s father’s efforts to help Indians flee the country. Can you tell us more about why you included his character?

Akello is a complicated character because he isn’t just your standard villain in the story. He too has a story, and it’s his story that drives the choices he makes in his life. We see his loyalty to Yesofu in the beginning, but that quickly changes when Yesofu continues to support his friendship with Asha. I wanted readers to be challenged by this character because there are times that you don’t know whether to like him or if he will change.

When Asha hides her family’s passports, I just cringed. And the end result of that is tragic. How did you decide what the ending should be? I’ll be honest, I kept holding out hope right until the final page, even though I thought you skillfully, hauntingly foreshadowed the presumed outcome when Yesofu and his father discover a dead body in the lake. Did you consider alternatives?

When I started this story I always knew that Asha would leave Uganda with her mum and sister and never wavered from that ending. I purposely left the ending somewhat ambiguous for readers to draw their own conclusions as to what happened to Asha’s father. In writing this story, I left pieces of myself within the pages, but once a reader opens the book, they bring pieces of themself to those same pages. By leaving things somewhat open, I trust the reader to draw their own final conclusions.

Well, if you as the author say it's still possible, I won't give up hope of the family being reunited later! Yesofu struggles with whether his gain has to come at Asha and her family’s expense. In your Author’s Note, you note that today, “many Africans now own and manage schools, universities, hospitals, shops, resorts, and large enterprises,” which is the hope Ugandans searched for in Amin’s expulsion order. Do you have any answers for Yesofu, and all of us? How could this end result have been achieved differently?

The roots of this historical event lie in colonialism and the effects it had on both Africans and Indians, while the British governed Uganda, and even after. This is where we can understand the motivation behind President Amin’s goal to provide opportunities to the African people. After all, Uganda was their country.

The horror lies in his actions. Those atrocities can never be justified. While writing this book, I wondered if the same outcomes could have been achieved differently and sooner if Idi Amin hadn’t been president.

Yesofu and Asha’s friendship is tested throughout the book. In early drafts, I maintained their friendship to the very end, but ultimately that wasn’t realistic. While Asha gains insight toward the end, it is already too late. For Yesofu, his world with Asha is very different from the world he wants for himself and for his family. This places him at odds with her. It is easier to let her go since she is leaving the country. I don’t think it would have been so easy if she’d stayed.

I’m often asked by young readers if Yesofu and Asha meet again. I don’t know the answer, but I think about the two of them meeting as adults and wonder what lives they would have built for themselves. Would Yesofu have gone to college? What country did Asha end up living in . . . England, Canada, Australia?

Such fun questions. And wise lesson. Before we go, we have one last question. What are three books you’d recommend to readers who enjoyed Orange for the Sunsets?

There are so many, but here are three of my favorites: Other Words for Home, by Jasmine Warga; When Stars Are Scattered, by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed; and The Night Diary, by Veera Hiranandani.

Wonderful. Thank you, Tina, for visiting with us and sharing with our community about Orange for the Sunsets.

Thank you again for inviting me to spend a little time with you and the Bookroo community. It has been a lovely visit.